by Romina Ciulli e Carole Dazzi

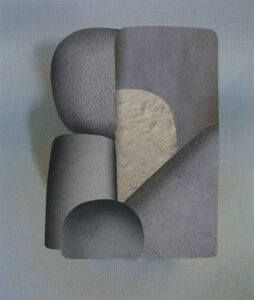

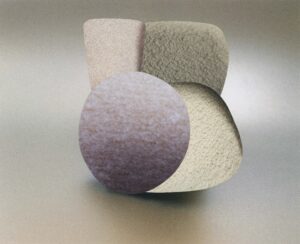

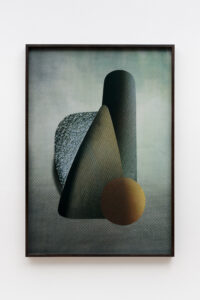

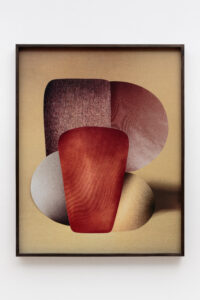

The value of the photographic image reviewed through the abstract language of collage. The works of the British artist Hannah Hughes consist of assembled and deconstructed parts with the aim to examine in depth the meaning of a modern visual culture that seems more than ever fragmented and artificial. Using materials extracted from books, newspapers, advertising images and even catalogues of auctions, Hughes’s work actually tries to recreate new specular shapes of just as many reproduced images, but that they similarly find a concrete position in the physical world. It is a figurative universe builded by means of a real archive of images collecetd over varied years, where later on each collage is assembled, concealed, recomposed and decorated in order to hide the original subject and move it within a new visual form. In this way our perceptions acquire a sense of reality, or truth, that seems to be deceptive, distorted, but at the same time it is revealed in its most conceptual and deepest meaning. This research emerges particularly in The Flatland Series work, which title is inspired by the novel Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions written by Edwin A. Abbott and that it takes place in a two-dimensional realm. Here a new two – and three-dimensional spatial perspective causes a visual tension through the combination of conflictng aspects: linear and sculptural compositions, misleading and credible, original and deconstructed. Let’s talk with the artist.

Your work is mainly based on the artistic tecnique of collage. Can you tell us about this choice and about which creative approach do you use for deconstructing your works? Particularly, how do you choose the material to assemble?

I initially used collage to make sketches for works in other media but it soon became the primary focus of my work. I started to cut out and reassemble the spaces surrounding objects and figures in magazines, auction catalogues and books, the so-called ‘negative’ shadow-spaces of the image, which could be visually activated when placed against other photographic images. This became the Flatland series of collages, which provided the framework to explore speculative ideas of transformation using throwaway found images. In my recent work over the past two years, I make collages from new photographs created by projecting shadows from cut magazine fragments. The interplay of positive and negative forms and processes is at the core of the work. It is a way of looking at our relationship to space – asking how space is represented in images, and how it can be manipulated through physical alteration and the imagination.

In these last years photography has assumed a more and more prominent role within the digital culture. As a consequence, even art often makes use of this medium in order to experiment a new vocabolary of visual forms that seem to go beyond the borders of space and time. So how much photography influences your artistic process?

I am very interested in how images exist in the memory as fragments, and how this might relate to the ways that we process photographic images in digital spaces. My approach is primarily a material response to the photograph, and it heavily involves the hand, cutting, re-arranging, and discovering what happens when one image touches another. I was first drawn to photographic images through reproductions in books and magazines and my work often responds to the ways that the image transforms through various print processes and repetition.

In your works the images are fragmented and transfigured, the lines are repeated in a obsessive way but are never identical, and the geometrrical shapes appear irregular and abstracted. These are decontextualized objects that seem to dissimulate their own phisical and material meaning, concealing and recomposing a conceptual universe that cause a sense of alteration and disorientation in the audience’s perceptions. What kind of message and emotion do you try to instill through your work?

I like your reference here to dissimulation — concealment is key to how the collages work, creating enough gaps in the image that it remains active. I think of this as a kind of restlessness, aiming to create images that appear to still be in flux. I am really drawn to the ways in which museums accumulate and display fragments from the past, and how these are often presented in their incomplete state to speculate on the original object. The gaps can be more interesting, where the imagination gets to work. My work largely acknowledges the impossibility of coping with the enormous scale of images that we sift through on a daily basis, and processes the image fragment like a memory, subject to fusion and revision. Hopefully it also conveys a sense that more interesting things can happen outside of the main centre of the action, on the edges.

In your works the use of soft and pastel colors often emphasize a sculptural attitude of the object. Consequently the sculptures seem to acquire an antithetical position inside the space, in this way they produce a perceptive tension between the negative value of the original image and the positive value of the re-elaborated image. How this conceptual perspective characterizes your research?

Photographing sculptures involves decisions about the optimal point of view, but a locked aspect often flattens the sculpture. I am fascinated by the impulse to look behind the photograph, and a lot of the tension between positive and negative spaces within the work (created through mirroring, inversion, refraction and repetition) is there to explore how to move around or travel through the image. For example, I have recently made a new sequence of larger 2-part collages (Tuck I,II and III, 2020). In these works, one photographic image is wedged through a cut in the surface of another. It comes from a process of thinking about edges, gaps, and the desire to see around the corner, as well as highlighting areas where one image supports or conceals another.

In 2018 you took part in the exhibition A Romance of Many Dimension at the London’s Sid Motion Gallery together with other artists. Can you tell us about this experience?

A Romance of Many Dimensions was a group exhibition with artists Abigail Hunt and Matthew Barnes. The title of the show was taken from Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, which had also provided a literary starting point for my work in the exhibition. All of the works in the show operated between two and three dimensions, between the flat image and the sculptural form. This was the first time that I showed one of the wallpaper works alongside my collages — this was a photographic vinyl wallpaper, printed with a non-repeating ‘pattern’ of black and white shapes cut from magazines. The wall work was an index for the collages — many of the shapes on the wall could also be read in the relief surfaces of other works in the exhibition. I am continuing to develop wallpapers, working with an accumulation of glyphs that can be interpreted as language or potentially a form of notation.

Which are the artists who inspired you during your artistic path or from who you are currently inspired by?

There are way too many! I often refer to Brancusi’s photographs of his studio being an important reference for me, which I first encountered in a second hand bookstore. I’d always been interested in his work, but this was the first time that I saw a sculptor defining the specific importance of context between works and the surrounding space through photography. There are many artists that I refer to who have worked with collage and fragments in various ways, and I’ve been looking recently at Al Loving’s incredible textile wall-hangings from the 1970s and rag paper collages of the 1980s. Miria Schapiro and Judy Chicago’s identification of “femmage” (any artwork created by women by assemling objects, as by collage, photomontage, etc.) was very influential, and relates to my use of ordinary materials similar to those found in the home, such as paper stocks used to make magazines, or paper pulp packaging cartons in my sculptures and photographs. I’m currently looking at Lygia Pape’s experiments with mirroring and positive and negative forms, an during lockdown I was researching seriality, repetition and the transformative use of everyday movements in the works of minimalist dancers and choreographers Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown.

Can you tell us about your future projects?

I have a new work in a two-person show ‘Gleaners’ with artist Olivia Bax at Sid Motion Gallery, London. The show takes its title from the practice of gathering leftovers, and includes sculptures, collages, and photographs that make use of discarded materials.‘Gleaners’ is available as an online catalogue during November and will open after the UK lockdown ends. https://www.sidmotiongallery.co.uk/

Biografia: Hanna Hughes (born in 1975) is an artisti working with collage, sculpture, constructed photography and moving immage. She graduate from the University of Brighton in 1997 and has since exhibited in the UK and internationally. Group exhibitions includes among others: “Where One Form Began Another Ended” (two person show) The Bakery Gallery, Vancouver, BC, (2016); “Concealer”, Peckam 24 Festival, curated by Tom Lovelace, Copeland Gallery, London (2018); “A Romance of Many Dimension”, Sid Motion Gallery, London (2018); “The Office of Revised Futures”, Format Festival, Derby (2019); “New Formations”, Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago, USA, (2020); “The State of Things”, curated by Rodrigo Orrantia, Landskrona Festival, Sweden, publication and axhibition 2020/2022; “Super Flatland” curated by Paul Carey-Kent and Yuki Miyake, White Conduit Projects, London, 2020; and “Gleaners”, a two-person exhibition with Olivia Bax at Sid Motion Gallery, London, Nov 2020-Jan 2021. Her work is included in an experimental publication by Rodrigo Orrantia, “Material Immaterial”, which has included performances at Cosmos, Arles and Offprint, Paris. Her work has been published in the FT Weekend Magazine, AnOther.com, Art Licks Magazine, the RPS Journal, Trebuchet, and the British Journal of Photography among others.