Written by Valentina Biondini, literature amateur

Our column “Who’s Next?” turns the attention to a woman whose artistic style had the power to change contemporary art forever. We are talking about Eva Hesse, an American sculptor of Jewish origin who, during her short career, reinvented and revolutionized the language of sculpture, making use of a chaotic aesthetic process, bordering on the eccentric, in which emerge intensely the notions of physicality and sensitivity.

In fact, her artisitic works are considered pioneering, as they are created with industrial materials such as latex, fiberglass and plastic, making her famous all over the world. Her fame has survived intact to the present day. She is also known for inaugurating the post-minimalist artistic movement in the 1960s. To better describe her artistic path, let’s first take a look at the most salient stages of her short and tormented life that deeply influenced her way of conceiving art. German jewish, Hesse was born in Hamburg in 1936. In ’38, at the age of two, she is sent by her parents, together with her elder sister Helen, to Holland, in an attempt to save them from the Nazi fury. The family reunited after about six months of separation and moved first to England, then in ’39 to New York, in the Manhattan area. But quiet is temporary. In fact, in ’44 her parents separated and two years later her mother committs suicide. At sixteen, Hesse graduates from the New York School of Industrial Art. Then she changed several Universities until landing at Yale, where she studied under the guidance of Josef Albers and was deeply influenced by the Abstract Expressionism movement. In fact, it can be said that on a pictorial level, the future artist is actually formed within this current, although later the attraction for the matter takes over.

In fact, her artisitic works are considered pioneering, as they are created with industrial materials such as latex, fiberglass and plastic, making her famous all over the world. Her fame has survived intact to the present day. She is also known for inaugurating the post-minimalist artistic movement in the 1960s. To better describe her artistic path, let’s first take a look at the most salient stages of her short and tormented life that deeply influenced her way of conceiving art. German jewish, Hesse was born in Hamburg in 1936. In ’38, at the age of two, she is sent by her parents, together with her elder sister Helen, to Holland, in an attempt to save them from the Nazi fury. The family reunited after about six months of separation and moved first to England, then in ’39 to New York, in the Manhattan area. But quiet is temporary. In fact, in ’44 her parents separated and two years later her mother committs suicide. At sixteen, Hesse graduates from the New York School of Industrial Art. Then she changed several Universities until landing at Yale, where she studied under the guidance of Josef Albers and was deeply influenced by the Abstract Expressionism movement. In fact, it can be said that on a pictorial level, the future artist is actually formed within this current, although later the attraction for the matter takes over.

After graduating in ’59, she returned to New York where she began to hang around with many young minimalist artists. Among them, Sol LeWitt, with whom she establishes a strong friendship and starts a close correspondence. It is precisely LeWitt, in a letter from 1965, who encouraged the then doubtful Hesse to experiment a completely personal artistic path, writing her to stop thinking and just doing. We don’t know what course the sculptor’s career would have taken if these words had not been addressed to her. The fact is that both have become important artists and their friendship has been a motivation to their mutual artistic development. In ’62 she married the sculptor Tom Doyle. Three years later the couple moved to Germany so that Doyle could dedicate himself to an artistic residency. For about a year Hesse and Doyle live and work in a former textile factory in the Ruhr area. The building, despite being abandoned, still contains parts of machines, tools and materials belonging to its previous use. And it is here, among the disused machines and tools, that Hesse finds the inspiration for her first mechanical drawings and paintings. Her first sculpture is also made here: a bas-relief characterized by ropes covered with fabric, electric wires and masonite, and entitled “Ring Around Arosie”. This is a turning point in the artist’s career. In fact, from this moment on in each of her works she will begin to use unconventional materials. In addition to the fact that they all will be characterized by a three-dimensional aspect, and a deep connection between touch and vision.

Although this relevant aspect, it should be underlined that the artist had not welcomed the return to Germany, the nation which, as the art critic Arthur Danto said: “only two decades earlier would have killed her without thinking for a second”. But, ironically, it was exactly there that her original artistic experimentation begins. A formal experimentation carried out, again to quote Danto, «playing with worthless material among the industrial ruins of a defeated nation». Hesse is best known for her sculptures. Actually, her first works (from the five-year period 1960-65) consist of abstract drawings and paintings which are often considered as mere preparatory works for subsequent sculptures. However, today it is believed that those drawings are a separate corpus and therefore worthy of evaluation in and of itself.

In 1965, once her return to New York, she begins working with unconventional materials, those that would later become the stylistic signature of her works: latex, fiberglass and plastic. In particular emerges the interest in latex. For Hesse, in fact, it was a means that had to do with immediacy and allowed her to create sculptural forms in an original way. As in her first two works Schema and Sequel (1967 – 1968), where precisely this material is used to create smooth but at the same time irregular and wrinkled surfaces. The 1960s were also heralds of professional goals. Indeed, her works (paintings, drawings and sculptures) are displayed in exhibitions of the highest level, at home and abroad. In 1968, her first entirely personal sculpture exhibition was organized at the Fischbach Gallery in New York, entitled “Chain Polymers“, which represented a milestone in her career, ensuring her an international reputation.

Unfortunately, everything stops at the end of ’69, when she is diagnosed with a brain tumor that led her to death within a year at the age of 34. The fate that seems to have become favorable, thus returns to show her its ferocious side. In this regard, Hesse once wrote: “Life does not last, art does not last“. Yet, at least for her case, the adage “Life is short, Art is long” would seem more appropriate. Yes, because the cult of her art didn’t stop at all with her death. Already since the 1970s, dozens of posthumous exhibitions have been set up both in the United States and in Europe. In the 1990s, retrospectives were organized in Valencia and Paris. Not even the dawn of the new century has wiped out the interest in this artist. In fact, the list of exhibitions dedicated to her work lasts at least until 2010. While the documentary directed by Marcie Begleiter entitled “Eva Hesse“, focuses on the story of her “tragically shortened life”, dates back to 2016. To date, more than twenty of her works are kept at the New York Museum of Modern Art. And outside the United States, the largest collection of her productions can be found at the Wiesbaden Museum (in Germany). We therefore have to ask ourselves what are the reasons that still keep the fire of interest in her art alight. To find the answer is necessary to appeal to a variety of reasons. First of  all, Hesse was among the few female artists of her generation to practice the technique of sculpture and one of the first to move from minimalism to post-minimalism. Indeed, though showing some of the typical elements of minimalism (simple shapes, delicate lines and a limited color palette), her work is based on repetitions and simple progressions that give life to an eccentric, unexpected result that resists uniformity, so much to be often defined “Anti-Form”. However, when the artist talked about her art, the adjective she used more often was “absurd”, considering it among other things its greatest quality. This is a concept that is linked to a procedural method that allows to get out of established schemes. But it also refers to something that, through a continuous repetition, lets you create without effort.

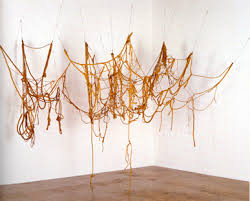

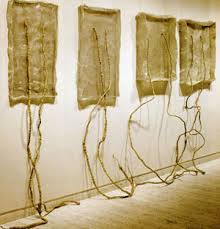

all, Hesse was among the few female artists of her generation to practice the technique of sculpture and one of the first to move from minimalism to post-minimalism. Indeed, though showing some of the typical elements of minimalism (simple shapes, delicate lines and a limited color palette), her work is based on repetitions and simple progressions that give life to an eccentric, unexpected result that resists uniformity, so much to be often defined “Anti-Form”. However, when the artist talked about her art, the adjective she used more often was “absurd”, considering it among other things its greatest quality. This is a concept that is linked to a procedural method that allows to get out of established schemes. But it also refers to something that, through a continuous repetition, lets you create without effort.  In fact, the repetition that distinguishes her works added more absurdity to the absurd, in a kind of obsessive progression with an even wider range. Furthermore, her works are conceived in relation to verticality and they visually establish a relationship with the wall that can be defined as “front-parallel”. As for the unconventional materials used (latex, rubber, resins, polyester and other plastics), Hesse had the ability to use them in a way never seen before, causing a feeling of amazement and immediacy in the the outside observer. In fact, distancing herself from minimalism, the sculptor conducts her research to the limits of the conventional and, through a process of repetition of forms and meanings, she creates an object that cannot be catalogued or classified.

In fact, the repetition that distinguishes her works added more absurdity to the absurd, in a kind of obsessive progression with an even wider range. Furthermore, her works are conceived in relation to verticality and they visually establish a relationship with the wall that can be defined as “front-parallel”. As for the unconventional materials used (latex, rubber, resins, polyester and other plastics), Hesse had the ability to use them in a way never seen before, causing a feeling of amazement and immediacy in the the outside observer. In fact, distancing herself from minimalism, the sculptor conducts her research to the limits of the conventional and, through a process of repetition of forms and meanings, she creates an object that cannot be catalogued or classified.

Hesse was also among the first artists to experiment with the fluid contours of the organic world of Nature, and some historians who studied the female art have considered it as a latent and proto-feminist references to the woman’s body. On the contrary , others have observed how the artist’s work brings to light, in a movement predominantly dominated by men, women’s issues, but outside of any political context. But Hesse always denied that her art was strictly feminist, defining it rather simply female, since, as stated in a 1970s interview: “Excellence has no gender”. For other experts, her works are a delicate shell within which they recognize a burning feeling, hints of lyricism and introspection opposing the aseptic and plastic rigidity of the forms. So, this important contemporary protagonist not only stands between the great season of minimalism and that of post-minimalism, but she does it in her personal way, bringing her own original contribution which insists on a tactile and bodily sensitivity, and on notions such as identity, subjectivity and gender. A contribution anticipating trends that will develop in the following decades. In fact, even modern-day sculpture uses many of the loops and asymmetrical constructions she pioneered. The last reason, certainly not least, of her undying success lies in contribute to change the approach to sculptural practice forever. The extreme ductility of the materials used allowed Hesse to create installations poised between organic forms and ethereal presences. In other words, hybrid works with the power to evoke an element and its opposite, chaos and order, material and immaterial, such as to be defined like “chaos structured as non-chaos”.

Hesse was also among the first artists to experiment with the fluid contours of the organic world of Nature, and some historians who studied the female art have considered it as a latent and proto-feminist references to the woman’s body. On the contrary , others have observed how the artist’s work brings to light, in a movement predominantly dominated by men, women’s issues, but outside of any political context. But Hesse always denied that her art was strictly feminist, defining it rather simply female, since, as stated in a 1970s interview: “Excellence has no gender”. For other experts, her works are a delicate shell within which they recognize a burning feeling, hints of lyricism and introspection opposing the aseptic and plastic rigidity of the forms. So, this important contemporary protagonist not only stands between the great season of minimalism and that of post-minimalism, but she does it in her personal way, bringing her own original contribution which insists on a tactile and bodily sensitivity, and on notions such as identity, subjectivity and gender. A contribution anticipating trends that will develop in the following decades. In fact, even modern-day sculpture uses many of the loops and asymmetrical constructions she pioneered. The last reason, certainly not least, of her undying success lies in contribute to change the approach to sculptural practice forever. The extreme ductility of the materials used allowed Hesse to create installations poised between organic forms and ethereal presences. In other words, hybrid works with the power to evoke an element and its opposite, chaos and order, material and immaterial, such as to be defined like “chaos structured as non-chaos”.

It is no longer a mere industrial object, but perhaps a new type of unstructured one, which contains randomness and confusion. In fact, it should be underlined that Hesse‘s works have often been at the center of debates, as they represent a real challenge for art conservators. However the materials she uses (except for the fiberglass) age badly. Their perishable nature makes them very fragile, which is why they can rarely be moved from one exhibition to another. And someone wondered if it was the artist’s intention to make them last or not. She once wrote to some collectors: “[…] when people want to buy it, I think they know, but I want to write them a letter and say it won’t last.” Yet the dedication reserved to materials and their transformation process seems to contradict such a position. Whatever it is, despite the unstoppable aging of latex, Hesse’s work vibrates and relives in every artist who has been influenced by her. For this reason she can be rightly defined as one of the mothers of contemporary sculpture.