by Romina Ciulli e Carole Dazzi

Monica Carrera’s artistic work is characterized by a minimalist language through which she investigates themes related to humanity, personal experiences, and the environment we live in. A conceptual art, indeed conceptually empathetic, intimate, and collective, achieved through the use of various mediums, but particularly photography. In fact, her photographic images are hybridized with other expressive forms and, transforming into installations or sculptures, they give life to true narrative works.

In this way, her shots become a means to narrate the individual and his reality, made up of social, public, and private relationships. Her many projects include QIC – Finestra su Calvino (2023), Sott’acqua (2022), …E pur si muove! (Still Alive) (2021), and Per una geografia erratica delle nuvole (2019). Let’s talk with the artist about her works.

Your artistic language is characterized by a conceptual, minimal, almost theoretical approach. A constructive modus operandi, which begins with the conception of the work and culminating in the conceptualization of the image itself. This aesthetic exploration ranges from photography to sculpture, from installation to video, from collage to a wide variety of materials, such as wood or linen. Can you tell us how this creative process unfolds? And what do you want to communicate to the viewer?

Actually, it has a strong connection with thought. It is, in fact, characterized by a very slow processing time. I could say that my works are visual solutions to the problems I face every day. As if something that wasn’t working in the world suddenly appeared before me. Something like a puzzle. And the work is the translation into image not so much of that solved puzzle, but of what emerged during its analysis: the structure of the problem, a different way of posing it, a different way of telling it. And this opens the door to possible solutions, which, for each of us, are unique. For this reason, I need to be eclectic in my use of techniques and tools. I believe my language always remains the same, even when the media used vary. As you have aptly defined, it is a lean but very precise vocabulary, undoubtedly indebted to conceptual and minimal art.

For example, when I created the series “Per una geografia erratica delle nuvole (o del diritto nomadico degli esseri viventi)” and “Del confine” – both from 2019 – I was wondering about the fuss made about migrations across the Mediterranean, about the right or otherwise to have a border, about the degree of permeability of this border to those who hold more or less valid passports, about the fact that man is born nomadic and has only been sedentary for a very short time… All these thoughts were whirling around in my head, and the result is a series in which I photograph transitory and changeable elements (clouds, water, an unmade bed…) sewing borders onto them, with all the violence that repeatedly piercing a photographic print entails in our culture. In one of these images, the embroidered border cuts the bodies in half, just to follow the contours of the land. To return to the focus of your question: I observe a lot of what surrounds me, from the micro to the macro. I ask myself questions, and problems, aporias, and contradictions emerge within me. The works I produce are the fruit of the process of analyzing these questions, which often have to do with human beings, their existence in the world, their perspective on the world, relationships, the power relations and coercion/normalization that a supposed majority exercises over a supposed minority.

Photography is the preferred medium of your work. Furthermore, images are usually combined using collage or other techniques. In this way, what we see goes beyond the simple, fleeting snapshot and becomes, through a constant exploration of the medium, a true gaze on what surrounds us. A gaze that becomes narration and, consequently, personal and collective reflection. How much has photography influenced your art?

I confirm, photography is my preferred medium. I’m not a photographer, but I’m deeply intrigued by photography as a process. I love her early work characterized by infinite shutter speeds and the use of painted backdrops: the former inspired “Istantanee (t →∞),” while the latter gave rise to the exotic collages of “Fa Ruggine.” I grappled with its extensive use as a tool for biographical documentation in “Homage to Cindy Sherman (performed by my mother)“, where I explored my mother’s biography and metamorphosis, raiding the albums where she collected photos from the 1960s to the present day. A period in which the way of shooting, the films used, and the printing methods have changed dramatically. So, while I explored my mother’s metamorphic changes, I also explored those of photography. I selected a series of images and simply placed them side by side like pearls on a necklace. In the second part of the work, I then contemplated the remaining gaps, the missed opportunities within a life.

I concluded the work by taking photographs of closed albums, almost a requiem for objects that are disappearing and, in a few years, will no longer exist. That said, I don’t limit myself to reflecting on techniques or their development, but I also explore their internal narrative potential. I’ve always felt the way I take photographs is extremely similar to the way images are formed or memories emerge in our memory. For me, the photograph oscillates between a fleeting glance and a mental image. Over time, perhaps also as a result of its progressive dematerialization, it has lost its status as a document, as absolute truth, increasingly taking on the tones of an ephemeral and arbitrary image, which immediately disappears or is submerged by others. This is why I cut them, sew them, juxtapose them, with the same ease with which our mind—or our unconscious—makes cut-ups, juxtapositions, and blends.

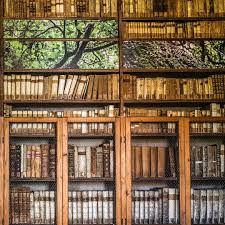

The installation QIC – Finestre su Calvino (2023) is a site-specific installation created inside the Queriniana Library in Brescia. The work, inspired by the writer Italo Calvino and his novel Il barone rampante, is composed of a series of photographs inserted between books, creating the idea of an opening, a sort of window onto the real and vegetal world. Therefore, once again, we find the concept of gaze which, in this case, seems to offer us a particular narrative vision, different from the character himself. Can you tell us about it?

The work stems from the almost physical perception I had when thinking about Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò, suspended among those branches – with his body – and among the books he read and longed to read – with his mind. The only way to convey the baron’s wild gait was to convey – by distributing it throughout the rooms, at different heights, allowing it to peer between the books – the baron’s almost animalistic gazes, no longer just man, but not just animal either. Drawing on the wisdom of both, he is a creature that transcends the nature-culture dichotomy to reach directly into the beating heart of life and experience. I captured these vegetal visions as I moved through Calvino’s Liguria, a beloved land, among its woods and its ruggedness, and brought them back to the heart of Brescia, which is home. I was looking for a way to reconcile two modes of being that also corresponded to two geographies for me.

On the contrary, in Sette sott’acqua (2022), the word is the fulcrum of your artistic research. It is an installation created with the images of seven teaspoons taken from the other, beneath which we see seven words printed in relief. The work, completed by an audio that plays overlapping sentences, analyzes the relationship between the thought, the internalized word and the communicated, diffused and externalized word. Can you tell us how this project was born? And how do you think the perception of the word influences our experience?

This work is a development of the previous work “Sette cucchiaini per la fine del mondo“. After identifying seven words (different in content, sensorial area, and grammatical category) that I would like to survive the end of the world, I had them engraved on seven silver teaspoons, ready to make the reverse journey: instead of emerging from the human mouth, they enter and become mute, silent, internal. But they also become nourishment. “Sette sott’acqua” explores what happens when these words enter, go “under water.” Under water alludes to the interior dimension, but also reminds us of the element in which we also are mute, like fishes. What happens when we are silent and the words remain inside? First, they become white, absolute.

Then they gain prominence and stand out from the background. From that prominence they begin to reverberate, to germinate. They mingle with each other and generate new sentences, new beginnings. As long as they are chosen carefully from the start. The audio that accompanies this sort of silent primer, reproduces – read by the neutral, post-human voice of a computer – these new beginnings that gradually overlap until they generate a sort of white noise. However, the word, pronounced endlessly, loses its meaning. It is as if I were paradoxically bringing the two extreme dimensions of speech to bear: the silent, internal one, for myself alone, and the open one, destined to become a breath for others. To answer the second part of your question, I believe that words often inform us, in the sense that they determine our form and the form of our actions. The reality we believe we move in is nothing more than the most credible story we tell ourselves. Consequently, I firmly believe in the power of words, both those spoken to us, but especially those we use to tell ourselves what happens to us.

The word is also at the center of another installation, Sette cucchiaini per la fine del mondo (2021), where each spoon is engraved with a word that you would like to remain as a testimony to humanity after the end of the world. The idea is that these words, rather than being sounds, become the experiential nourishment of a collective grammatical and sensorial universe. Can you tell us how the idea for this project was born and how you chose the seven words to be engraved?

The work was born as part of the project “L’ultimo appartamento” that I created with two other artists and a curator, in which we were asked to stage an exhibition in a disused apartment. It was December 2021 and, seeing this cold, abandoned apartment, we imagined to describe it as if it were the last refuge before the apocalypse. The works were mixed with real objects and furniture, with which we recreated the feeling of a long-abandoned house, almost like a wreck found by chance. Creators and archaeologists at the same time. In this setting, the teaspoons found even more meaning: they were placed in an orderly row and glistened on an old wooden table in what was once the kitchen. There I took the photograph you find in “Sette sott’acqua.” The idea of the words remaining after a traumatic experiences comes from a text I loved very much by the author Georgy Gospodinov, “The Phiyics of Sorrow”, in which a character returns from the war with, as his only loot, seven words in Hungarian. So I asked myself what seven words I would take with me as loot for a new world, as a legacy of what has been. It wasn’t easy to choose them, and they don’t claim to be exhaustive. I looked for words that belong to different grammatical categories (abstract nouns, concrete nouns, common nouns, proper nouns, verbs, interjections, etc.) and which relate to different sensory areas:

SONG: a masculine noun that refers to sound, but also the form of the verb to sing, Homer’s “I sing” opening the Iliad and epic poems in general. FLOCKS: A collective noun that prompts us to raise our eyes to the sky and observe a movement that lasts the beat of an instant. ULYSSES: a mythical character, symbol of the man who made wandering his way to learn, with the dual meaning of learning by wandering and learning by making mistakes. FEET: a concrete noun that brings our gaze back to the earth, to the pace of walking, to the slow movement of wandering, to searching. HUNGER: an abstract noun that refers to a separate sensory area, the seventh sense, the burning sensation that drives us to move from a lack. It is what has characterized human experience from its appearance on earth to the present day. With the name MARCH, I wanted to allude to spring without being literal, to its buds, to its cyclical nature, to its eternal return. Finally, GOODBYE was necessary: it refers to somewhere else, to a farewell with the hope of finding oneself in another world—to God—perhaps man’s greatest invention, the true counterpart of Ulysses.

The photographic images of …E pur si muove! (Still Alive) (2021) tell the story of some deserted homes, almost haughty in their rigidity. Houses that nevertheless seem to come to life, becoming the object/character from which wild hair emerges. Therefore, a contrast between what is inert, inanimate, and what seems animated by its own, almost uncontrollable will instead. Why did you choose hair in particular to create this work?

This work is a Work in Progress, its rhythm determined by the growth of my hair. This year, too, as my hair grew, I enriched the series with new works. It originated during the period of confinement at home due to the pandemic. The desert I saw the few times I went out, reminded me of the kingdom shrouded in brambles after Sleeping Beauty fell into a deep slumber that lasted a hundred years, following the pricking of the spindle of the enchanted spinning wheel. The slumber had spread to all the inhabitants, and only the bramble bush seemed alive, slowly enveloping the village. I still clearly remember the Disney book that depicted it, one of the first of my childhood. So I imagined a very long pandemic, all of us asleep as if dead in a modern-day Macondo: only our hair grew in this magical immobility, only it was allowed to emerge, overflow, become a jungle. In my imagination, foliage is strongly linked to the wild and, as such, also represents what escapes our control and escapes us, despite ourselves: energies, emotions and much more that is invisible to the eye.

Let’s talk about Pettine d’acqua dolce (2022) and Sciogliere nodi (2021), two works that can be defined as somehow related. They are, in fact, two sculptures, made with wood and other materials, alluding to the power of objects as medicine. How much does popular tradition influence your artistic research?

Very much so. It has a powerful language, entirely similar to that of contemporary art. A language that should speak to our unconscious. A. Jodorowsky, the inventor of psychomagic, speaks of art in one of his texts and is very clear about this: art is that which has the power to germinate, to give life. In this powerful relationship with life, popular tradition finds its true key. I would also add that I have a true passion for primitive art, which has much in common with popular tradition: the relationship with the sacred and the belief that images can influence the real world. In this, I oscillate between the primitives and Louise Bourgeois, with her famous phrase “Art is a guarantee of sanity.”

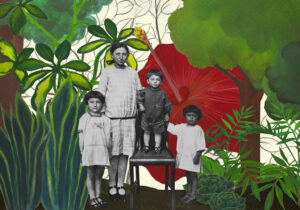

In your work there are two pieces in which installation and photography take on a strong conceptual narrative function, Fa ruggine 1 (Il desiderio non realizata non perdere d’intesa, fa ruggine) (2015) and Fa ruggine 2 (2015). The first is composed of an iron structure in the shape of a boat with a tree inside, while the second uses different backdrops to create actual collages. However, in both cases, what emerges is a reflection on the human instinct to leave and the instinct to stay. Can you tell us about these projects?

I created these works in 2015, the year in which, with the Case Sparse artist residency project we set ourselves the goal of exploring the river, one of the three environments that characterize the place (Malonno, Val Camonica). The Oglio flows there, the same river that, many kilometers away, also passes through the place where I was born. For me, water has always been a symbol of movement and displacement, and it is a theme that often recurs in my works. Malonno and the entire Val Camonica, like Italy as a whole, was affected by powerful migratory flows between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The local historian told me that nine out of ten children left.

Perhaps because at that time I was experiencing firsthand the conflict between the desire to move elsewhere and the personal issues that prevented me from doing it, and I identified with the one who stayed home. With a rusting desire, imagining the others in who knows what exotic worlds. Thus was born a cage-boat whose mainmast has living roots. A sort of lowercase monument dedicated to those who remain, in which the instinct to travel and the fear of cutting off one’s roots coexist crystallized. The collages, on the other hand, were born from a fascination with the use of painted backdrops in early photography. As I mentioned before, identifying with the one who remains, I imagined those who had left living in exaggeratedly exotic, almost psychedelic worlds. So I painted backdrops myself on which to display the photographs, recovered from the municipal archive, of those who had left.

In the photographic series Per una geografia erratica delle nuvole (o del diritto nomadico degli esseri viventi) (2019), and in the series titled Del confine (2019), the more or less arbitrary concept of borders, both social and private, is analyzed. This abstract representation, however, is identified on photographic paper by embroideries that appear labile, unstable. To what extent can these limits influence our experiences and our human relationships?

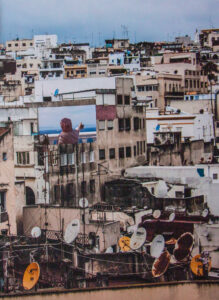

It essentially depends on who you are, but above all where you were born and how rich you are. As I said in one of my previous answers, borders change their permeability depending on the strength of your passport, which largely depends on the wealth of your country. If you were born on the wrong side of the world, allow me this somewhat crude expression, it’s not even that easy to leave. I also touched on this theme in the collage series “Le antenne di Tangeri guardano il mare” (2020), created during a stay in Tangier, on the Strait of Gibraltar, thirty kilometers offshore from Spain.

In the evening, the wind carries the voices of Tarifa, its lights can be seen in the distance, but the inhabitants know full well that they can only access it with a day visa. The medina of Tangier is narrow, perched, and striking for the enormous number of satellite dishes that surround it, almost a wall of ears that act as a shield but at the same time receive and capture the images of the Western world. On the other hand, I saw many people stopping and gazing at the sea: static images, perhaps of suspended desires, of listening, of other attunements. Here, the sea is not only a distance to be crossed, but also the distance between the reality of a world and its fictional representation. Once again, we find the desire to cross the border – the situation of the children of Tangier trying to cross by clinging under trucks is emblematic – and the impossibility of doing so coexisting in the same image.

Are there any artists who have influenced your work or who continue to inspire it?

Without a doubt. I’m aware of some, probably not of others. So I can only mention the first, starting with my great loves. Formally, but not only, I believe I owe a great deal to F. Gonzales Torre and Louise Bourgeois. I love the brilliance and formal solutions of H. P. Feldmann. I’m indebted to much minimal and conceptual art, as well as to many photographers who, without me realizing it, have shaped my gaze (F. Woodmann, the Bauhaus photographers…). Among contemporary artists, I literally have a passion for the punk and tragic world of J. Benassi, the grace of S. Camporesi, the irony and synthesis of W. Prieto. I already know I’ve forgotten many of them.

Can you tell us about your future projects?

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on time and the ability of stone to preserve it, capture it, bear witness to it. In this regard, I recently completed “A mano a mano“, an installation composed of seven marble soaps, each engraved with a word that refers to what we would like to wash our hands of because it is too painful, too shameful, too unbearable. Sometimes even just to defend a small shred of happiness besieged by the tragedies of others. However, what we wish to erase today like soap, with the passage of time becomes marble in our memory and consciousness. Today is the time when we can act, feel, and look as witnesses, without turning our heads, both in the face of small individual tragedies and in the face of collective tragedies. The seven soaps, one for each day of the week – almost as if renewing the daily ritual of a different forgetfulness – are made of precious marble in pastel colors and are intended to resemble in every way the scented soaps we bring home from a trip to the French Riviera or buy at the local supermarket. But they carry significant weight and indelible inscriptions. Where much of our present is written on luminous screens, stone remains a guarantee of eternity.