by Valentina Biondini, art and literature amateur

Vera Pagava (1907-1988) was the first Georgian female artist to gain recognition in the European art world. She was a well-rounded artist, devoted herself to drawing, decoration, and especially painting over the course of a fifty years career. She emigrated to Europe with her family in the 1920s, shortly before Georgia’s annexation by the Soviet Union. First, she settled in Germany and then in Paris, where she remained for the rest of her life, while maintaining strong ties to her homeland.

Her works, characterized by abstract motifs, still lifes, and timeless landscapes, silent figures, and fairytale atmospheres, are captivating for the purity of their compositions, in which forms and colors are perfectly balanced, while her characters move between reality and imagination, mythology and biblical tales, creating fantastical universes and narratives.

The 1930s were a decade of experimentation, including murals and fabric designs. Instead on a personal level, in this period she met Vano Enoukidzé, another exiled Georgian artist, who proved to be her soul mate. During World War II, and particularly after the German invasion and occupation of France, Pagava explored biblical themes, as if she was trying to address the difficult historical moment through religious themes, perhaps the only ones capable of evoking the biblical proportions of the unfolding tragedy.

1944 was a turning point for the painter, when the Galerie Jeanne Bucher exhibited some of her paintings alongside those of Dora Maar, Picasso’s companion, in a successful show that established her in the Parisian art scene. This period’s paintings are reminiscent of post-Cubism and avant-garde artists, reworked in a personal manner, with essential patterns and a dark, restricted palette that expressed her desire to remain essential. Critics agree that her work gradually shifted from figurative to abstract between the 1930s and the 1960s. In particular, from 1960 onward, she no longer needed the “crutch” of figuration and painted predominantly geometric shapes with rounded and irregular edges.

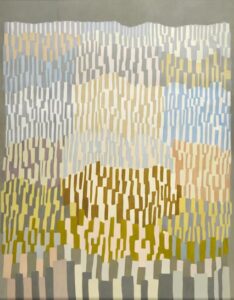

In the final phase of her career—the artist passed away in 1988 in Montrouge, a small town near Paris—interiority dominated the external world, and abstraction triumphed in a celebration of color and form. Her latest works are, in fact, characterized by geometric shapes depicting stars, skies and mountains: simple “celestial bodies” that appear as the graceful manifestations of an intimate and spiritual cosmos. It should also be remembered that her experiments draw on the avant-garde movements that preceded her and also served as inspiration for those that followed. For example, the silhouettes of her battle scenes, such as “The Fall of the Angels” (1953), recall Matisse’s various “dances” and also prefigure the folded colored arabesques that Simon Hantaï would have created ten years later. Meanwhile, in her city series, she experiments with interlocking colored rectangles, and similar formal explorations can also be found in Robert Delaunay’s Simultaneist works and Piet Mondrian’s Cubist works of the 1910s. Thus, her large canvases, such as the almost monochromatic “Presence” (1963), echo Mark Rothko’s atmospheric monochromes.

Today, her memory is carried on by the Vera Pagava Cultural Association and the retrospectives at the Galerie Darial, which she founded with her childhood friend Tamara Tarassachvili. Her legacy is one of the rare artistic practices in which the Georgian pictorial tradition, especially evident in her early works, not only transforms into modernism, but also represents the intersection of two seemingly distant worlds. If we were to ask her, in a deceptive way, to talk about herself for the Who’s next… column, here’s what she would tell us…

Paris is where I’ve lived for many years now, but it’s not my homeland. Wherever he goes, an exile will always carry with him the memory of his homeland, and an exiled artist will always carry with him the art of his native country. This is why my work can best be defined as a fusion of modernist references, that is, of my time, and Georgian references, that is, of my personal history. And this is why for so many years I never wanted to take French citizenship. I shared this decision with my friend, the gallerist Tamara Tarassachvili, who, in the 1970s, founded the Galerie Darial, with an exhibition of my paintings. The name Darial was not chosen by chance, it is a pass that marks the border between Russia and Georgia, a symbol of resistance and independence for Georgian people.

When art critics discuss my work, they always note the progressive transition, over time, from figurative to abstract. In fact, I realize that, although I felt a call to abstraction from the beginning, only at a certain point I did strongly sense within me that “I could no longer manage figuration and that I no longer needed to use it as a crutch.” And also that “I could no longer tolerate figuration and I no longer needed to use it as a tool.” In other words, I understood that abstract forms allowed me to best express my desire to be independent as an artist because they freed me from all expressive constraints.

As my career progressed, my works were described as spiritual, as the product of my inner world. And I must admit that, yes, for me the relationship between art and spirituality is very profound. I would say, in fact, that “painting reflects us, it is a miraculous mirror in which the outside world sees our inner world” and that “talent is the means of communication between us and life, humanity, heaven and earth.”

Ultimately, I can say that the goal that has guided my artistic research has been none other than “seeking the absolute by translating light into color,” and I truly hope that even today my rarefied and luminous painting, similar to a foggy day invaded by the sun, still has something to whisper to those who observe it.

Thank you Vera.