Written by Valentina Biondini, literature amateur

In the second episode of the “Who’s Next?” column, we are going to focus our imaginary camera on an Italian woman who successfully moved into the fields of screenplay and direction, in the first two decades of the last century. This woman goes under the name of Elvira Notari and she is universally known as the first Italian film director and one of the first in the world (together with Alice Guy-Blaché, French director and film producer).

Elvira was born in the city of Salerno in 1875, she graduated at the Scuola Normale (the future teaching schools)and, after moving to Naples with her family, she started to work as a milliner. Here she meets Nicola Notari, a former painter specialized in coloring photographic films, who becomes her husband in 1902. The couple gives birth to three children and … a film production company! This is the Dora Film based in the city of Naples, the very heart of the Notari family’s business.

At that time the film industry moves its first steps. Instead of industry, however, it is more appropriate to talk about artisanal cinema, both for the techniques used (the frames were often hand-colored one by one) and for the storytelling and acting (the great schools of dramatic art are not founded yet, therefore it proceeds through experiments and attempts). It is silent cinema, of course.

Unexpectedly in this initial phase, the feminine element has a considerable weight not only among those who are involved in coloring films and editing, activities considered suitable for women because similar to sewing. In effect, there are many female actresses, directors, producers and directors of drama schools.

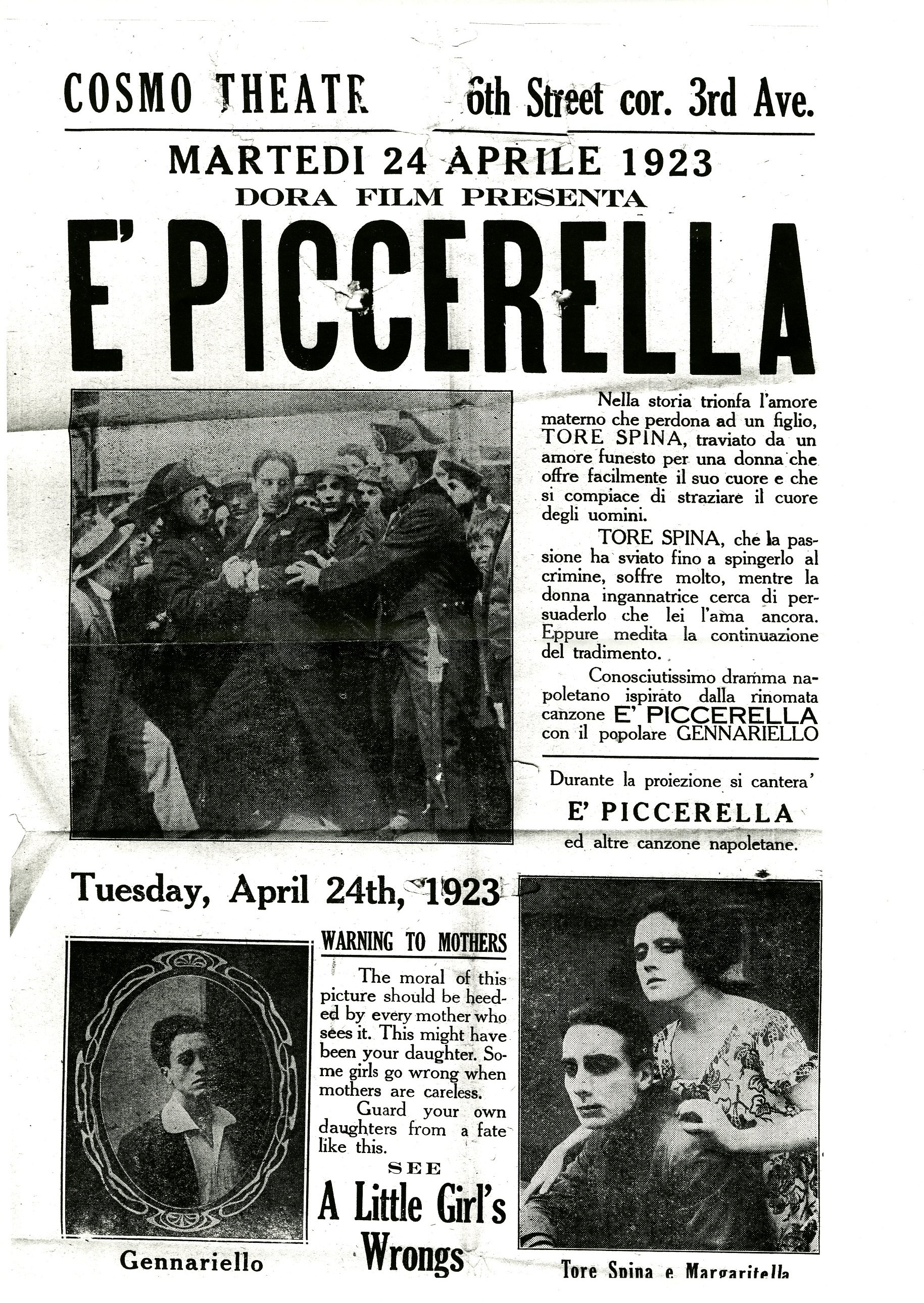

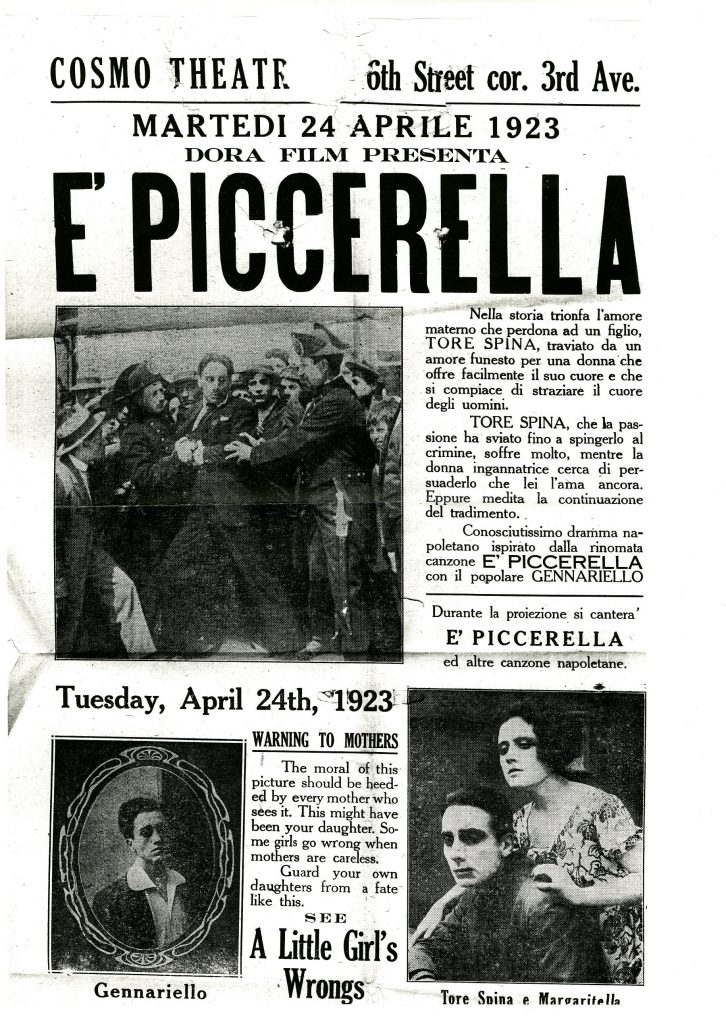

From 1914 Elvira starts to personally oversee the entire creative cycle of the Dora Film productions, leaving the technical part to her husband Nicola. So she begins to write, direct and promote all their films, adopting systems that are surprisingly close to those of nowadays marketing. As for this last point,in fact, Elvira buys the rights of the best songs of the Piedigrotta Festival and make them sing live during the film showings, paints the posters and gives interviews to the newspapers. In other words, she carries out activities that are not yet canonical, but that would have become fundamental in the film industry.

Her works can be classified as popular novels: they portray with rough realism the reality of Neapolitan slums, the urchins and outcasts’s life. There are also many female figures, never passive women, on the contrary almost fatal, who try to get out of the space they traditionally belong to, the domestic one. They dream a different life, although often are not able to realize it completely. One of her favourite actress is Rossella Angioni, aka Rose Angiò, endowed with particular beauty and natural sensuality, who in real life is the teacher of her son Edoardo, who was also hired as the first actor in the Dora scripts. In short, her stories are full of love, sensuality and desire. Whilst her characters embody the passionate and contradictory soul of Naples, totally opened to life, both to its joys and its dramas.

Elvira even opens a drama school that is awarded in the “Concorso di arte muta” of Milan in 1920. On the set she is determined, stubborn, far from being submissive, so she earns the nickname “la Marescialla”. From her actors, mostly non-professionals and street people, she wants real emotions and to pull them out she also knows how to be cruel. According to what the say, Elvira spoke to a young orphan actor of his dead father in order to make him cry.

Notari claims a naturalistic way of acting, forerunner of Neorealism, similar to that adopted in later successful works like “Ladri di biciclette” (1946) by Vittorio De Sica. A style that clashes, however, with the nascent fascist censorship that does not want to hear about outcasts, madmen and other derelicts.

But Notari’s works find a warmer reception overseas in the community of Italian-American immigrants who, at least for the duration of the films,feel to be back home again. The luck overseas is such that, in the 1920s, Dora Film opened an office in New York, the “Gennariello Film”, in the Manhattan neighborhood.

Among her widest production – about one hundred short films and about sixty full-length films – only three survived up today: È piccerella (1922), ‘A santanotte (1922), Fantasia ‘e surdate (1927), kept in the National Film Library of Rome. Even “La cattura del pazzo di Bagnoli” (1912) was lost and it is a misfortune because it is considered as the first documentary film shot in Italy, a milestone in its genre. In it Elvira and Nicola record all the passages of Ciro Esposito’s arrest, a man guilty of crimes against public order, until his entry into the Capodichino mental hospital. The film is not only one of the first and most interesting “newspaper cinema” experiments, it especially shows the gap between the popular cinema based in Naples and that of Turin, its only Italian competitor of the time, focused on blockbuster and aimed at thriving US market (whilst Rome will not be among the great capitals of European cinema until the advent of Fascism).

In 1930, after about two decades of honorable activity, the Dora Film close its doors. On one hand, the interference of the fascist authorities is more frequent and invasive (they claim the right to preventively read the screenplays, cut the scenes considered “scandalous” and impose subtitles in Italian). The regime, aware of how cinema can play a central role in shaping Italian society, does not tolerate showing madness, suicides and unstructured families to the public. Thus many Notari’s films are branded as “anti-national”, for the benefit of the much more solemn and celebratory cinematographic works of the North. On the other hand, the Dora Film must surrender to sound, which is now advancing inexorably, and to a new way of making cinema, no longer artisanal but industrial and which will see, among other things, the gradual exit of women from the sectors related to production.

This feminine marginalization still continues today if we consider how unusual it is to find in the credits, even in the last film released in cinema, a female name next to the voices “director” or “script of”.

But Notari’s stubbornness and energy teach us that it is possible for women even to come out in sectors of almost exclusive male domination. Then we hope that the example of this capable and strong-willed woman will be rediscovered to a greater extent than today (and not just only among authorised personnel) and – why not? – celebrated maybe with a film: the art she loved so much and pursued during most of her life.